Getúlio

Angel and demon

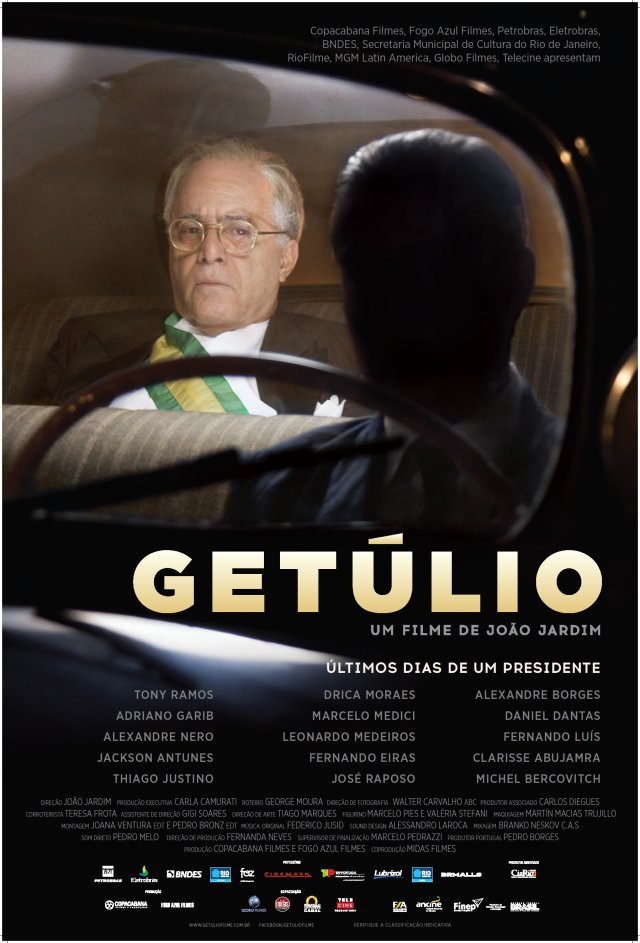

Certainly, the biggest challenge for any Brazilian filmmaker should be to make a movie about the one who was unquestionably the greatest leader of their country, Getúlio Vargas. But what if, in addition to shedding light on some aspects of his life, the film also raised some discussions about the Brazilian way of doing politics? This seems to have been another quality of the movie “Getúlio” (BRA, 2014), directed by João Jardim, and with Tony Ramos in the lead role.

Many wonder why explore the life of a president who died seventy years ago? Getulio led a coup on the grounds that he was robbed in the elections and forced a revolution using the death of his vice-presidential candidate – who was a man opposed to violence. He was someone who valued his country and wanted to preserve it from the spoliators. He was extremely skilled in dialogue with opponents and political allies, almost always the same. In other words, if we do not study history, we will always repeat the mistakes of the past …

At first, we can imagine that the greatest difficulty in taking Getúlio Vargas to the screens is the enormity of his life and work. How can we speak, in less than two hours, of a man who was an unyielding dictator and at the same time creator of worker protection laws? Someone who sailed well both among the many fascist leaders of his time and among the so-called Democrats? A man idolized and execrated by Brazilians even decades after his death.

There were many events in which he was directly linked: The Revolution of 1930, the Constitutionalist War, the Estado Novo, the game of cat-and-mouse with the great powers during The Second World War, the creation of Petrobras and the National Steel Company, the overthrow by military coup and the return by popular vote, etc..

Any of these events would fit perfectly as the subject of a film. Perhaps that’s why the filmmakers hit the fly by defining as the object of the movie the impactful nineteen days between the attack of Toneleros Avenue and his dramatic death, which would delay in ten years a new military coup.

Although idolized by much of the population, Vargas had enemies outside and within the government, hoarded throughout a lifetime. Greatly weakened by age and poor health, surrounded by a sea of corruption, what is observed in these last moments of his life is the relentless hunting driven by the most conservative sectors of society, who used slander as a weapon, with the strong and happy collaboration of the great press – something that has not changed over all these years.

It would be impossible to forget that, for a long time, Getulio ruled the country with an iron fist, establishing a regime that closely resembled that of Hitler’s Germany and Mussolini’s Italy. In his favor, we must remember that until World War II, a large number of countries were ruled by dictators, and even democratic countries like England tyrannically controlled large colonies such as India and several African countries.

Getulio also had a populist side, creating labor laws that still exist today, in a country where official slavery had been abolished a few decades earlier, and most workers were kept under critical conditions.

This same warlord, which even abolished state and municipal flags in the Estado Novo, manouded as a fox the influence of the warring countries in The Second World War, obtaining exceptional conditions for an underdeveloped country of the time.

In the current film, we find a broken Getúlio Vargas (Tony Ramos), a president who to govern needed to make a deal with countless parties, very different from the powerful dictator who had been in the past. Every day there were new scandals, true or false, but which were repeated to exhaustion by the press, mainly by the newspaper Tribuna da Imprensa, by his fierce enemy Carlos Lacerda (Alexandre Borges).

It was involving Carlos Lacerda that began the crisis that would change the course of Brazil’s history. In the early hours of August 5, 1954, a shooting attack killed major Rubens Vaz of the Brazilian Air Force (FAB), and injured, in the foot, Carlos Lacerda. The attack was attributed to members of the personal guard of Getulio, called by the people “Black Guard”.

The political crisis that took place was very serious because, in addition to the importance of Carlos Lacerda, the FAB, to which Major Vaz belonged, had as a great hero brigadier Eduardo Gomes, whom Getúlio had defeated in the 1950 elections. The FAB created a parallel investigation of the crime, which ignored the other institutions, and which received the nickname “Republic of Galeão”.

The newspapers and radio stations made an intense coverage of the persecution of the suspects, as well as the interrogations that included Gregório Fortunato (Thiago Justino), head of Vargas personal guard, accused of being the mastermind of the attack on Lacerda.

In this hostile climate, increasingly threatened by a planned process of exection and public humiliation, Vargas had few loyal friends, among them Tancredo Neves (Michel Bercovitch) and his daughter Alzira Vargas (Drica Morais).

More than staging a well-known story, the direction of João Jardim and the production of Carla Camurati built a political thriller with an intense pace, showing to the new generations that certain misfortunes, such as the performance of the press at the behest of unethical interests, and the behavior of political parties was not new at the time, and it remains common practice even today.

Even notable was Vargas’ ability to submit to self-sacrifice, overwhelmingly reversing the plan of the enemies, and causing a ten-year delay in the military coup that was being designed. According to his words, “he came out of life to enter history.”

This movie is available on the Netflix streaming service.