The Twilight Samurai

Soul of wood

Anyone who follows this column must have already noticed my admiration for oriental cultures, especially the Japanese one. This extends, of course, to the movies. The curious thing is that when I ask for an example of a samurai movie, people quote, most of the time, “The Last Samurai” (USA, 2003) and some even risk “The Seven Samurai” (“Shichinin no samurai”, JAP, 1954) by Kurosawa. These are the most enlightened, as some suggest films by Jet Li and even Jackie Chan. But, a good example is “The Twilight Samurai” (“Tasogare Seibei”, JAP, 2002), although it totally escapes the gender stereotypes.

Although widely used in cinema and even in games, the iconic figure of the samurai is poorly understood, mainly by Western optics. Samurai, which means “the one who serves” was a civil servant who had functions such as collecting taxes or administering land for a feudal lord, the daimyô. In feudal times he gained military assignments and was the main soldier of the imperial aristocracy. This figure remained until the last decades of the 19th century, when Japan suffered a great and overwhelmed modernization.

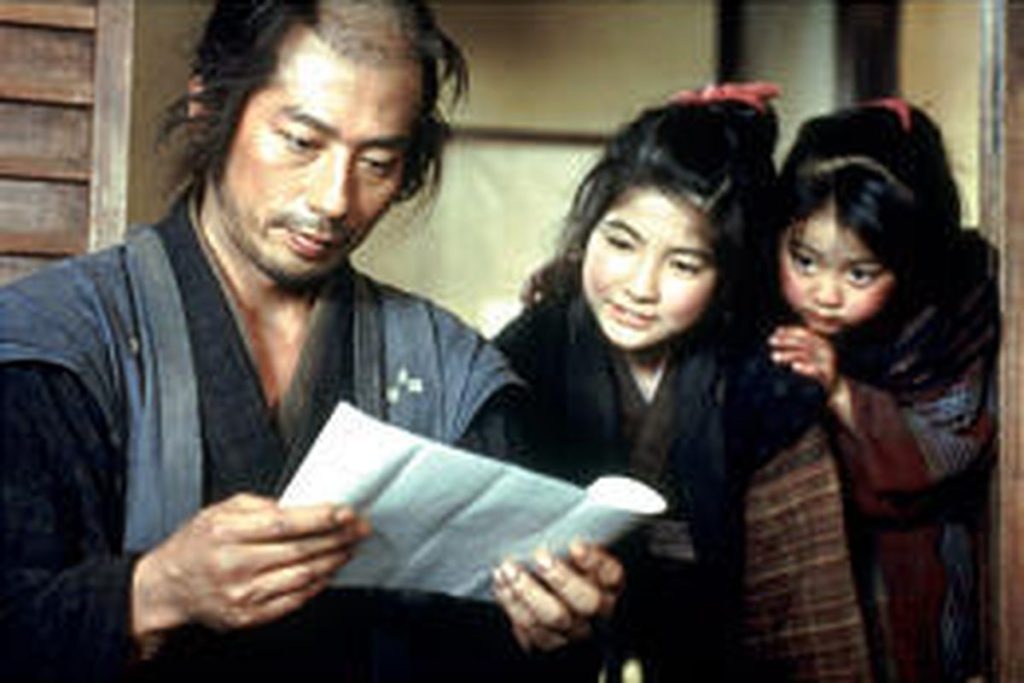

In the heart of feudal Japan, Seibei Iguchi (Hiroyuki Sanada, who would later do the guy who used to beat Tom Cruise in “The Last Samurai”) resembles very little the figure of the heroic and elegant samurai. Widowed, messy and dirty, he had a bureaucratic post at the castle of his master, being responsible for the food supply.

Seibei, unlike most colleagues, was extremely poor. A prolonged illness of his wife and the following funeral led him to assume heavy debts, and to honor them, he committed the most dishonorable act for a samurai: he had sold his long sword, the katana, considered the “soul of the samurai”.

A man dedicated to his family, Seibei struggled to keep his daughters studying, emphasizing the importance of knowing how to read and understand Confucius, while taking care of his mother, who suffered from a degenerative disease, to the point of not recognizing him. To improve his income, he manufactured cages for birds, activity that also accursed, since to the rigid feudal Japanese society, only peasants and servants did handicrafts.

The hope of a new life appears when Tomoe (Rie Miyazwa), sister of his best friend and an old love from childhood, returns to the family, fleeing the husband who mistreated her. But the social difference, even between samurai families, and Tomoe’s ex-husband are very difficult barriers to overcome.

When Seibei confronts the arrogant husband armed only with a wooden stick, his fame as an expert swordsman runs the world, and he is practically forced to face a dangerous ronim, a samurai without a master, who refused to surrender.

“The Twilight Samurai”, by director Yôji Yamada, is a beautiful example of the cinema of a country that always oscillates between high technology and the maintenance of ancient traditions. Very different from most martial films that flood the market, full of incessant fights, this movie, with two prosaic confrontations, prefers to explore other fundamental values of Japanese culture, such as the feeling of honor, the love of the family and the respect for traditions.

Although it is not clear to most Western viewers, the plot, like “The Last Samurai”, takes place in a delicate moment in the history of Japan, when the figure of the samurai and the country’s social structure is questioned. And the title of the movie refers not only to the protagonist, but also to the sunset of an era that lasted a thousand years, but that was coming to an end.

Even privileging the dramatic part, “The Twilight Samurai” caught the attention of international critics, being among the nominated for Best International Feature Film at the Oscars 2004, and at the Berlin Festival 2003. As a negative aspect, only the slow, smooth rhythm, typical of Japanese cinematography, which may displease audiences more used to action blockbusters.