The movie that wanted to be a book

Since its invention, just over a century ago, cinema has established itself as a catalyst for other arts, bringing them all together in making a film. It is not difficult to understand this when thinking about how a scenario uses painting and sculpture, music permeates the entire work through the soundtrack, and dance and theater help to compose the performance of the cast.

Much associated with the movie is also the literature, which often gives rise to the story that will be told on screen. To get an idea of the importance of this relationship, there is an Oscar category, that of Best Adapted Screenplay, which rewards films that have best adapted books to cinema.

This association with literature comes from the beginnings of cinema, although the fifteen-minute film reels greatly limited what could be shown. Subsequently, the industry evolved and the duration of the movie depended on how much the producers were willing to spend on it.

One aspect that is fundamental, and that we cannot ignore, is that cinema and literature have different languages. Often a banal scene in the book takes on impressive dimensions in a movie, as is the case with the famous wizard chess scene in which Ronnie must win in order for Harry Potter to reach the philosopher’s stone.

The size of the book also does not need to have a direct relationship to the length of the film. Érico Veríssimo’s monumental work “The time and the wind” (“O Tempo e o Vento”), which spans ten volumes, was used in different films, which focused on parts of the collection. The films “The Besieged House” (“O Sobrado”,BRA,1956), “Ana Terra” (BRA,1971) and “Um Certo Capitão Rodrigo” (BRA,1971) were extracted from it, as well as a 210-chapter novel, “O Tempo e o Vento” (1967-1968) and still a miniseries for television of the same name in 1985.

Sometimes there is a “cinematographic fraud”, when it is announced that a film is based on a famous book, but what appears on the screens brings a very different version, or just a small part of the original work. Fans of author Philip K. Dick always complain about adaptations made from his works, such as “Blade Runner” (USA, 1982), “Total Recall” (USA, 1990) and “Minority Report” (USA, 2002). In addition to the author’s different view, these three films were based on short stories.

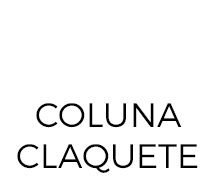

Other notable cases are “Papillon” (USA, 1973), whose story shown in the movie corresponds to less than the initial third of the book. Gabriel García Márquez’s work, “Love in Times of Cholera”, a novel with more than four hundred pages, was condensed in the eponymous film (USA, 2007) to a small part of the book.

Other films follow the opposite path, are made from short stories and have a well-developed history. This is the case with the films mentioned above based on short stories by Philip K. Dick. Two other examples that I liked a lot were “Babette’s Deast” (“Babettes gæstebud”,DAN,1987), based on a twelve-page short story by Karen Blixen, and “Arrival” (USA,2016), from an even shorter tale by Ted Chiang, “Story of Your Life”. And we could not forget “The Hobbit”, a simple book by J.R.R.Tolkien, which was transformed into three feature films by Peter Jackson.

This comparative look comes from a long time ago, because as a child I was fortunate to grow up in a family that loved to read, in addition to having a cinema less than a hundred meters from home. It is no wonder that cinema and literature are the arts I love most, and they have an even deeper relationship than people realize.

When I was studying Literature at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, a professor called our attention to the differences between a short story and a novel. The tale is small, dynamic, synthetic and specific. There are no redundancies, and any word anywhere in the text is related to the following content. In a novel, however, redundancy is not only allowed but also desired, to deeply characterize the characters.

Interestingly, when analyzing movies, I realized that they have the same qualities as the short stories. The film must have the necessary fluidity, without redundancies and repetitions, and any scene that appears must have a relationship with what comes next. Thus, a car that has difficulty in starting, or a certain tease of the character will be important for a later scene, nothing is by chance.

In a series or in a soap opera, the rules are more similar to those of the novel. As the time is longer, it is possible to build the character with characteristics that are repeated so that the spectator / reader will memorize and recognize that individual.

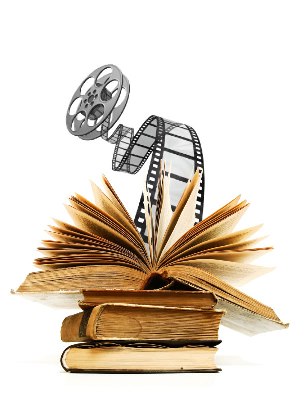

The other day I had an unusual experience, considering many decades of cinema and literature. Watching the film “The Movie of My Life” (“O Filme da Minha Vida”,BRA, 2017), directed by Selton Melo, I felt a certain discomfort throughout the exhibition. I found the film slow, with scenes in excess, and with unimportant characters. In the final credits, I discovered that the movie was based on the book of Chilean writer Antonio Skármeta, “Un padre de película”.

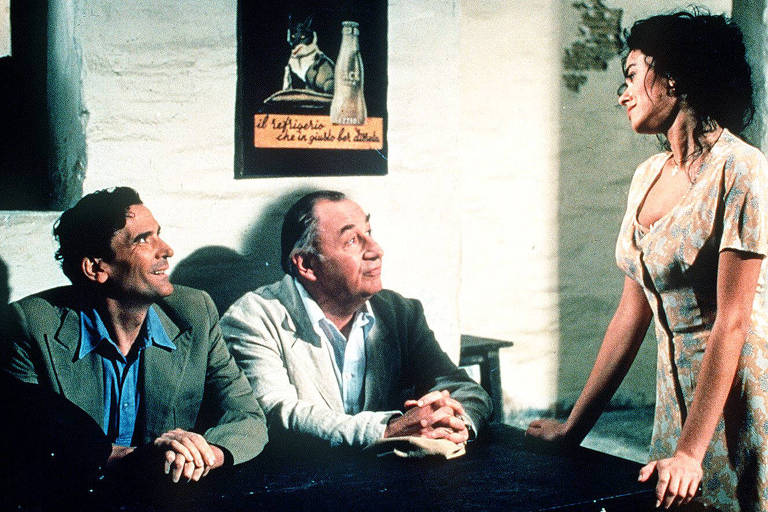

When researching more about the writer, I discovered that he was the author of the book “Ardiente patience”, which gave rise to the movie “The Postman” (“Il Postino ”, ITA/FRA,1994), winner of the Oscar for Best Soundtrack, in addition to four more nominations. Another book by Skármeta , “Los días del arco-iris”, inspired the movie “No” (Chile,2012), that was one of the finalists in the Best Foreign Film category at the Oscar 2013.

With so many good references, award-winning books and films, I was curious to read the book “Un padre de película” to see if my discomfort with the film made sense. When I read the original text, I proved what my feeling had denounced. The book is a masterpiece of conciseness and objectivity, with little more than a hundred pages in a simple and direct style, which refers more to a short story than to a novel.

The story of the book is much succinct than that shown in the film, and the scenes that I considered excessive do not even exist in the original text. The character played by Selton Melo in the movie had no importance in the book, and even the flashback scenes with the protagonist’s father (played wonderfully by Vincent Cassel) were added without much enrichment of the text.

In fact, if they spent any money on a script, it was a waste, because the book itself was already a finished script, with nothing to be removed or added. It is a pity to have to criticize a national film, even more so by Selton Melo, who has already lived great characters and directed good films and series.

Certainly, readers have already observed other cases of this relationship between cinema and literature, which varies from coherence to incoherence, from summarized to extended, from detailed to simplified. Like any relationship, there are moments of satisfaction and frustration, but the important thing is that we can always enjoy it. Even if it is only to criticize.